How much do looks matter on the campaign trail?

Photo: Liberal leader Justin Trudeau and his wife, Sophie Grégoire at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2008 (Richard Burdett/Wikimedia Commons)

By Caitlin Martin Newnham

“Nice hair, though” is the catchphrase of Canada’s 2015 federal elections. But it’s not just the phrase used by the Conservatives to attack Justin Trudeau’s luscious locks. The phrase represents the importance that citizens place on appearances when deciding who should lead them.

The emphasis of physicality in politics is a convention common to both Canada and the U.S. throughout history. Nelson Wiseman, the director of the Canadian studies program at the University of Toronto, explained that “physical appearance is very important (and) comes right down to the colour of the tie you wear in the leaders’ debate.”

Harper proved this theory several times during his incumbency. For example, Wiseman said, “On the ‘Three Amigos’ summit (a meeting with the leaders of the U.S. and Mexico), he was wearing a safari outfit and some fun was made of that.”

“Since then he’s picked up someone who lays out what he’s going to wear,” Wiseman said.

Clothing is an important factor in the appearance of politicians, but this election has highlighted one highly criticized feature of the candidates: hair.

Facial hair has been a focal point of appearance controversy in politics, so much so that Wikipedia dedicated an entire page to listing whiskered former U.S. presidents.

Abraham Lincoln was the first president of the United States to have a beard. His decision to abandon his smooth face for a chin curtain was allegedly influenced by Grace Bedell, an 11-year-old who wrote to Lincoln before he was elected. Grace told Lincoln his face is too thin: “All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be president.”

It’s clear that not everyone agrees with Grace because, as Wiseman pointed out, “Much has been written about Nixon’s five o’clock shadow during the presidential debate with Kennedy.” Kennedy was clean-shaven and composed in front of the cameras, whereas Nixon was uncomfortable and haggard-looking following his stay at the hospital for a knee injury. Kennedy won the debate.

Tom Mulcair, the leader of the New Democratic Party, has a neatly groomed beard that would have been commonplace during the inception of Canadian governance. Out of the 25 delegates at the Charlottetown Conference, 19 sported facial hair. In the context of the last century, however, the last whiskered prime minister was Louis St. Laurent who only had a whisper of a moustache.

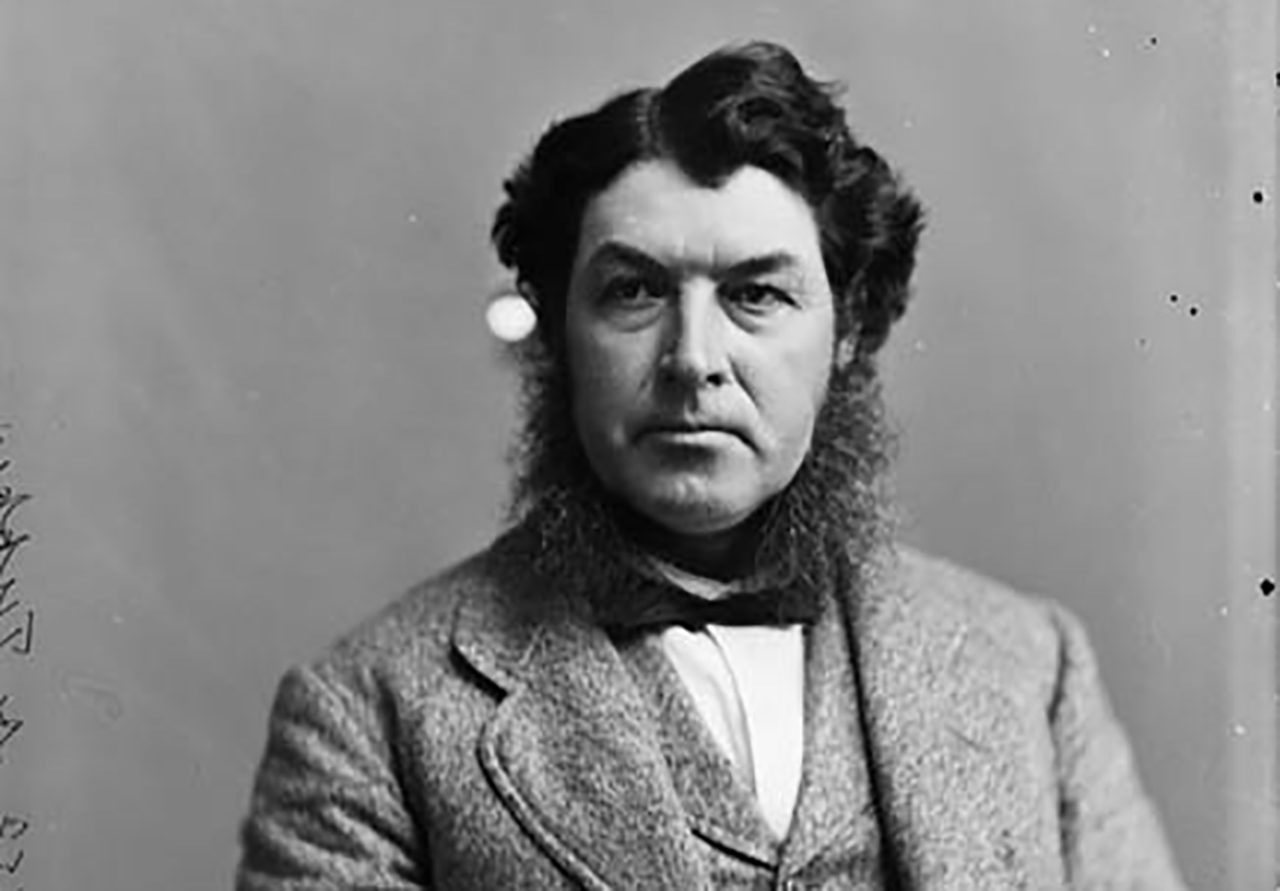

Amongst Canadian Prime Ministers, the prize for most impressive mutton chops undoubtedly goes to Charles Tupper (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

But Wiseman does not think Mulcair’s beard is necessarily bad for his campaign.

“Some women think beards are sexy,” Wiseman said, but some think facial hair is unpleasant. “(Mulcair’s) just being himself — if he changes people will ask, is he hiding something? … I think you’re best off being true to yourself, unless people say you look goofy.”

Justin Trudeau, the leader of the Liberal party, may be clean shaven, but the hair on his head ignited the recent conversation about the importance of hair in politics.

“(Appearance) influences a lot subconsciously, and sometimes consciously,” Wiseman said. “The reason why the Conservatives in their ‘just not ready’ ads used a picture with Trudeau and his long hair is because of his youth.” The Conservatives intended to emphasize Trudeau’s youth in the attack ad’s photograph and strategically followed the image with, ‘He’s just not ready.’”

But there is no reason for Trudeau to get a trim. “If you’ve been to your hairdresser and you don’t like what they did, you’ll feel awkward for the rest of the day,” Wiseman noted. “You exude more confidence and poise when you’re being yourself.”